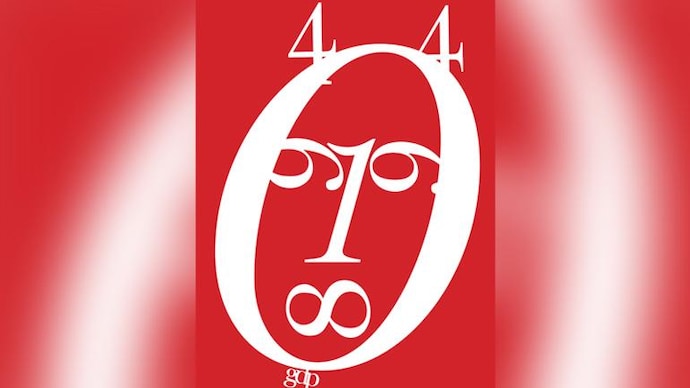

The Devil's in the Data

The new GDP back series released just months before the general election raises a political stink and threatens to erode the credibility of India’s economic data worldwide

I could end the deficit in five minutes. You just pass a law that says that anytime there is a deficit of more than 3 per cent of the GDP, all sitting members of the Congress are ineligible for re-election, Warren Buffet, the maverick investor, famously said. A ballooning fiscal deficit and sliding growth are every government’s nightmare. Data can make or mar reputations. In India, as the economy grows and diversifies, the problem of capturing the growth story in numbers has left policymakers flummoxed. GDP revisions are the norm, as are various other data revisions, including of industrial growth and trade, which form the basis of GDP calculation. Such revisions seldom create a stir, except when they impact past data and put a former government in dimmer lightas we witnessed last week.

The back series of the GDP for the years 2004-05 to 2011-12 has kicked up quite a storm, with some sections of the business media even calling for its withdrawal. The reason? The data throws up numbers which suggest that in the years when the previous government was in power, growth was lower than widely believed, and more importantly, lower than the growth record of the present dispensation. This statistical assertion has surprised economists and analysts alike, since it contradicts virtually all other data on the real’ economy, including on corporate sales, investment, credit growth and revenue from taxes, among others. The debate opens a can of worms in a country where both the dearth of data and the credibility of available data have become a matter of concern. For instance, the credibility of jobs data has been debated over. A new way to gauge job creation, by using data on new additions to the government’s provident fund scheme, has faced flak for not reflecting the actual situation on the ground. There have been conflicting theories on the impact of demonetisation, with the agriculture ministry first saying that the withdrawal of high-value currencies announced in November 2016 actually hurt farmers, only to reverse its opinion within days and put a question mark on the data used for the analysis. The biggest casualty of frequently changing or unreliable data are new investments, because investors cannot take a secured call on where to put their money. Frequent and drastic changes in data can send conflicting signals to investors, says D.K. Joshi, chief economist at ratings agency Crisil. For a country where private investments have been on the downslide for some time now, more unpredictability on data is a further dampener, which could prompt them to shelve investments or put their money and resources to use elsewhere.

THE GDP GOOGLY

The concerns that have arisen about the backdated GDP data under the new series, with 2011-12 as the base year (compared to 2004-05 as the base year earlier), are numerous, but the one that has caught many by surprise is the comparative data on the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) and National Democratic Alliance (NDA) years, now suspiciously resolved to render the NDA years superior. The new data says that the economy grew at an average 6.7 per cent in four years of the first term of the UPA government (2005-06 to 2008-09) as well as in its second term (2009-10 to 2013-14). This is lower than the earlier estimates of 8.1 per cent and 7 per cent average growth rate (calculated with 2004-05 as the base year), respectively. These growth rates are lower than the average 7.4 per cent growth rate (calculated with 2011-12 as the base year) seen during the first four years of the present NDA government. Experts have questioned some of the glaring anomalies in this calculation. For instance, growth during the economic boom’ of 2007-08 has now been downgraded from 9.8 per cent under the old series to 7.7 per cent under the new series. This is only a shade higher than the 6.4 per cent growth registered for the year 2013-14, the last year of the UPA government, which witnessed considerable turmoil, marred by Coalgate and the 2G scams, flight of capital and policy paralysis.

This back series issue has generated many more questions than it has answered, says Maitreesh Ghatak, professor of economics at the London School of Economics. I am not aware of any other country which uses these back seriessometimes you have to combine old and new series and there are standard methods of doing that. He says that anyone who deals with statistics knows that by choosing a suitable base year or suitable price deflator, one can have considerable leeway in terms of how one can make growth look in a particular sub-period. (A deflator is a value that allows data to be measured over time in terms of a base period, usually through a price index.) This seems a purely political exercise to make growth under the current regime look good, says Ghatak. And, yes, it does damage the credibility of our economic statistics, which is especially unfortunate because despite being a low-income country, India has a very distinguished history of producing high-quality economic statistics and enjoys worldwide respect for that.

If the performance of certain individual sectors was a key indicator of economic growth, then the UPA years clearly saw better growth than the NDA years. Reports suggest, for example, that the average annual growth in domestic car sales between fiscals 2005 and 2012 was 13.8 per cent, while it was just 1.1 per cent between fiscals 2012 and 2018. Two-wheeler sales growth in the first period was 11.6 per cent as against 7.1 per cent in the second. Growth in corporate tax was 21.5 per cent in the first period compared to 10 per cent in the second, while growth in non-oil exports stood at 18.4 per cent compared to just 1 per cent in the second period.

The average annual growth rate between 2005-06 and 2011-12 got reduced by 1.3 percentage points, from 8.2 per cent in the old series to 6.9 per cent in the back series. This is unprecedented, says R. Nagaraj, professor at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai. In any such exercise, it is important to check if the estimated values are broadly consistent with related macro variables, he adds. The reduction in GDP growth rates for the second half of the past decade does not seem to square with trends in saving, investment, foreign capital inflows, exports and so on, and hence the doubts about the veracity of the back series. The Central Statistics Office (CSO) should publish the details of the underlying methods and procedures in a transparent manner to silence the critics, adds Nagaraj.

Contrary to practice, CSO and NITI Aayog jointly held a press conference on November 28 to release the new series data, raising eyebrows. It’s a clear shift that the NITI Aayog got involved in the generation of the new series. One gets the suspicion that it was not done by professional statisticians, says Pronab Sen, a former chief statistician of India. Sen has criticised the series because it relies on value. For instance, if earlier the number of telecom subscribers was accounted for, the new series looks at the number of minutes consumed. I don’t think this is a better way of doing things. There has been no improvement in productivity or quality, adds Sen. Another economist, who did not want to be named, suggests that while the new methodology may be good, the data inputs are of poor quality. It’s like running a Ferrari on adulterated fuel, he says.

DATA POLITICS

Defending the new back series, Rajiv Kumar, the government-appointed vice-chairman of NITI Aayog, says that economists and researchers had been demanding it for the past two years and former chief statistician T.C.A. Anant had said that the new data would be released by 2017. However, because of several coverage and methodological challenges, the process took longer than expected. When the CSO approached me about the work they had done, I suggested that they should get it validated by senior statisticians. I approached the series as a professional economist, he insists. Kumar rattled off a list of five statisticians who were involved in the vetting of data before it was presented (see interview).

The growth estimates for the UPA years run lower than what was presented by Sudipto Mundle, professor and member of the board of governors at the New Delhi-based National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, in August. At that time, the government had dismissed the new back series GDP data as not official, an argument it maintains even now. Mundle had reportedly called the estimates the second-best option in the absence of comparable data for the years up to 1993-94. The new back series uses data from the ministry of corporate affairs and is technically compliant with the United Nations guidelines in the System of National Accounts 2008.

One possible explanation for the big change in numbers is inflation, which was much higher during the UPA regime, in turn inflating nominal GDP growth. The decline in inflation in the past four years, says Joshi, accounts for the difference between real GDP (GDP adjusted for inflation) and nominal GDP growth. Consumer inflation between fiscals 2006 and 2014 averaged 8.5 per cent as against 4 per cent in the past four fiscals. But many economists remain sceptical. Yes, it clearly has to do with the deflator that is used, says Ghatak. But the problem is that the real GDP growth rate in the UPA years under the original CSO figures looks pretty good too. It does so under the back series that the NSC (National Statistical Commission) generated a few months ago. So, it is not just a matter of inflation being higher under UPAeven though that is true. It has to do with the specific price index use under the very latest back series calculations.

Is real GDP’ the wrong way to measure growth? Real GDP is not the yardstick. It should be nominal GDP. And that will show a different picture, says Joshi. Nominal GDP growth averaged 10.5 per cent in the past four years, or 500 bps lower than the trend growth of 15.5 per cent in the previous nine years. This partly explains lower credit growth, corporate revenues and tax collections in the past four years compared with the earlier period.

The controversy around the GDP back series data has once again underscored the need for trustworthy data. Whether it’s jobs, trade or factory output, all talk about data comes with some scepticism. Add to that the new data dashboards on every ministry’s website, which make interestingly sunny claims, and the confusion is quite palpable.

CREDIBILITY CRISIS

To be fair, India has grown in the volume of data it is putting out. From rural housing to electricity to roads built, India has become a data nation’. But, little of this data has been presented in a time series. When you don’t have a time series, you start doubting the data. If there are drastic changes in a short span of time, say even 20 days, but no explanations provided, you will start ascribing a motive to it, says a macro economist who wished to remain anonymous. According to him, data on urban affordable housing is the worst, coming in with considerable irregularity. The government publishes a PDF document, which disappears from the site once new data is uploaded.

Yet, there have been several occasions when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government presented divergent pictures of the economy. EPFO (Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation) data has also come under scrutiny since early 2018 because of the massive revisions between the initial data and the final one. Economists say that for some data, there is roughly a 30 per cent downward revision from initial estimates. Trade data was massively overstated at one time, but that has improved.

India was once considered a data treasure for the rigour and detail with which economic information was presented. Broadly, the long-term series data that India has produced is available in very few countries. We have 60 years of granular money supply data, which represents a structural transformation. Even the ASI (Annual Survey of Industries) data is from the 1980s, which is very detailed, says an economist. However, some other critical data remains missing. I make a 100-slide presentation on the India story and I don’t even have one slide on IIP (Index of Industrial Production) data. None of us even looks at the industrial output data because of the way it is collected.

If the government presumes that the new GDP numbers would create a very positive perception about its economic performance, it is mistaken. In fact, the revised series will be of interest to a select few, while the general public will be largely unmoved by such a technical debate. What would truly interest the general public is the question of how ground realities are being addressedjobs, exports, more investment, better basic infrastructure, healthcare and education, to name a few. The kind of flip-flop we are seeing now will erode the credibility of our economic data, warns Ghatak. We should let the CSO do its job without any political interference. Meanwhile, India will have to invest a lot more in modernising its data collection and analysis if it is to hold on to the credibility it enjoys among the global investor community. Most importantly, it should not be perceived to be tweaking data to score political points, just months away from the general election.

NEW GDP SERIES VALIDATED BY TOP STATISTICIANS

Amid questions over the timing and motivation behind the new back series of the GDP, NITI Aayog vice-chairman Rajiv Kumar tells Shweta Punj that the data is credible, but he is open to exploring technically better alternatives in the future. Excerpts from an interview:

Q. What’s the motivation behind the new GDP series? Its release so close to the general election makes one think that the data could be politically motivated.

A. This is something economists and researchers had been demanding for the past two years. Former chief statistician of India, T.C.A. Anant, had said that the back series will be released by 2017, but the process took longer owing to coverage, methodological and other challenges. When the CSO (Central Statistics Office) approached me about the work they had done, I suggested they get it validated by senior statisticians. I approached the series as a professional economist. While I was at the Centre for Policy Research, I was a vocal critic of the old series. I had a two-hour-long meeting with Anant on it, after which I accepted that the new series represented a distinct improvement.

We held two meetings of the country’s leading statisticiansCSO and NITI Aayogbefore releasing the data. In the first meeting, some methodological problems came up and were corrected. Call me politically naïve, but I had no idea about the political implications. The statisticians who were part of setting the methodology and validating it include Anant, Professor Bishwanath Goldar (Institute of Economic Growth), Dr A.C. Kulshreshtha (deputy director general, Department of Statistics and Programme Implementation), Professor Chetan Ghate (Indian Statistical Institute) and Anupam Sonal (Reserve Bank of India).

Q. But this is the first time the NITI Aayog, or for that matter any other institution besides the CSO, has been involved in GDP data.

A. Since I had been a critic of the old series, as a professional economist, I was approached to look at the new series. There were two review meetings. NITI Aayog and the ministry of statistics and programme implementation work closely, so I didn’t see any reason for not joining the press meet on the release of the data.

Q. You have said you are willing to take a relook at the data?

A. I will engage with professionals like Professor R. Nagaraj (Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research), who has been a critic of the new series. Technically better alternatives will be considered in the future.

Q. The issue is that the numbers don’t seem to add up. How can we have growth while investments are down?

A. We are looking at this large body of macro-economic data. It’s not possible to reconcile that with every micro indicator. The issue is about trends in broad macro data. It is not right to compare the two. Growth rates can be similar with varying investment rates if capital efficiency has improved. We all know about capital-output ratios changing.

Q. India has a data problem. Input data is of very poor quality. How are we addressing the larger problem of data?

A. We need a lot more resources to strengthen our data system. National Statistical Commission chairman R.B. Barman has called for massive modernisation of data systems. It will be done.

Q. We now have a data credibility question looming. How will you pacify the naysayers?

A. The CSO is a highly professional and credible organisation. When you question the credibility of work of such technical nature, you have to prove it and not just indulge in rhetoric.